Clinical Trials

Although clinical trials are a substantial and rapidly growing international business, they are not well understood by the general public. They are often seen as obscure and are sometimes surrounded by controversy about the ethical aspects that touch the nature of the early side affects. Clinical trials are a systematic and rigorous procedure to distinguish successful therapies

and medicines from unsuccessful ones. Gradually, more structured experimentation began to take place. Experiments of the British naval doctor James Lind in the mid-eighteenth century were designed to discover the causes of scurvy, a disease that had decimated British naval crews. The experiments relied on comparative groups of men, giving one group vinegar and the

other group citrus fruits to treat scurvy. As a result of these experiments, which demonstrated the efficacy of oranges and lemons against scurvy, the Royal Navy began supplying citrus fruits to its ships in 1795. However, it took more than a hundred years from those early experiments for the modern system of drug testing to be born. While in the United States, not until 1938 did the U.S. Food Drug and Cosmetic Act subject new drugs to premarket safety evaluation and require Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulators to review both preclinical and clinical test results. However, even this law did not precisely specify the kinds of tests required for approval, so it gave regulators only limited powers for negotiation with the harmaceutical industry. Public health disasters caused by poorly tested drugs, such as thalidomide, showed that the system was not dequate to the task. The thalidomide disaster and other, similar ones ultimately prompted the passing of the 1962 Drug Amendments. Those laws explicitly stated that new drug approvals would rely on substantial scientific evidence of a drug’s safety and efficacy. Therefore, the FDA was obliged to base its approvals on “adequate and well-controlled studies.” The modern clinical trial, based on statistically controlled, evidence-based results, was born and eventually became the requirement for new drug approvals by the FDA. The FDA approval procedure is regarded today as a world standard of the drug industry. Preclinical studies involve two types of experiments: test tube ones, known as “in vitro,” and also experiments carried out with animals or cell cultures, known as “in vivo.” The experiments apply different doses of the drug under study to develop acute toxicity and toxicity ranges and to establish a pharmacological profile of the drug. The tests’ results inform the decisions related to granting the drug candidate with an investigational new drug (IND) status and open the way for further testing of the drug candidate under the actual clinical trials regime. Clinical trial (also called an interventional study), the participants receive specific interventions according to the research plan or protocol created by the investigators. These interventions may be medical drugs or medical devices; medical procedures; or applying changes to participants’ behavior. When a new product or approach s being studied, it is not usually known whether it will be helpful, harmful, or no different than available alternatives so the investigators work to determine the safety and efficiency of the proposed intervention by measuring specific outcomes on the participants. Generally clinical trials used in drug development are described or divided by phase. These phases (will be discussed later) are defined by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). A principal investigator usually led the clinical trial, a research team consists of doctors, physicians, nurses, and health care professionals’ works under the supervision of the

investigator. These trials take place in different locations hospitals, research centers, medical schools, and a community of health professionals. (“Learn About Clinical Studies.” Home. N.p., n.d. Web. August. 2012). Clinical trials are planned to add to medical knowledge related to the treatment, diagnosis, and prevention of diseases. To be precise:

Evaluating interventions for treating a disease, syndrome, or condition Finding ways to prevent the initial development or recurrence of a disease or condition.

Examining methods for identifying a condition or risk factors for that condition Exploring ways to measure and improve the comfort and quality of life of people with a chronic illness.

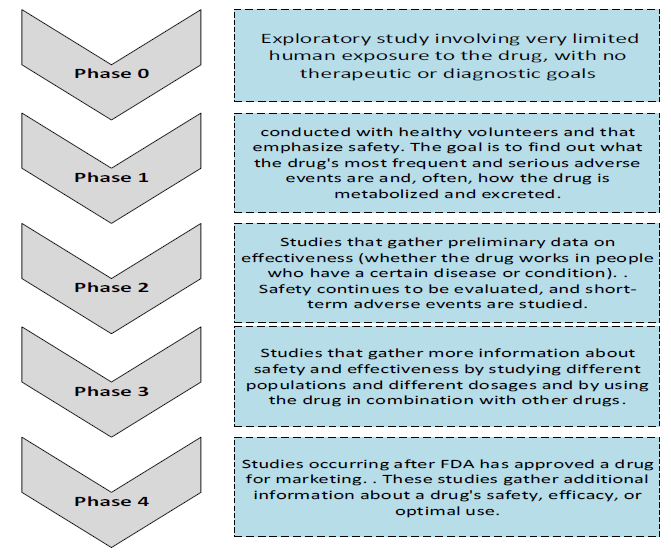

Figure 4 illustrates that actual clinical trials of a new drug typically proceed in four phases. Phase I trials constitute the first stage of testing in human subjects. Usually, a small group of 20–100 healthy volunteers are selected. Phase I includes trials designed to assess the safety profile and initial tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of a drug candidate. Phase II is performed on larger groups (100–300) of patients who have the disease the drug aims to treat or prevent, to determine preliminary effectiveness. This outcome is designated as confidence in mechanism (COM). Safety assessments that started in phase I are continued, but in a larger group of volunteers and patients to assess common short-term side effects and risks of the drug candidate. These safety tests should result in reaching a milestone called confidence in safety (CIS). Phase II studies are sometimes divided into phase IIA (related to frequency of dosing) and phase IIB (efficacy at prescribed dosage). Phase III trials expand upon the preliminary data for effectiveness and monitor longerterm safety to determine the overall benefit–risk profile in larger groups of patients. The results form the basis that informs the labeling information, which determines marketing elements of the new drug. Phase III is costly and usually constitutes the “pivotal trials” regulators weigh strongly in their approval or disapproval decision Phase IV in some scenarios, some clinical trial studies may need to be conducted as well as the larger ‘pivotal’ studies. However, if these studies are small may not be necessary before submitting for licensing approval but are conducted after approval and are called phase IV (O’Neill & Hopkins, 2011)

Figure 4. Clinical Trials Phases