Clinical features of AS

AS has a chronic disabling disease course and it affects multiple organ-systems. The onset of disease is predominantly in the teenage years and twenties. The onset at a young age exposes patients to a prolonged burden of disease. It is more common in men and has a male-female ratio of 3:1 (Dean 2014). There is a strong genetic component that accounts for more than 90% of the risk of disease. The presence of HLA-B27 antigen increases the disease risk and about 1- 2% of all HLA-B27 positive people develop AS (Khan 1980,Hammoudeh 1983). The disease causes inflammation of the sacroiliac joints and the axial skeleton. Sub-ligamentous new bone formation is another characteristic of this disorder. New bone formation results in ankylosis of the spine (syndesmophytes) (Zhang 2013). The disease severity of AS is strongly influenced by genetic components (Hamersma 2001). Extra-articular manifestations are also known to occur in AS. The common extra articular manifestations are acute anterior uveitis (25-30%), psoriasis (8-11%) and inflammatory bowel disease (Stolwijk 2014, Levy 2014, Brambila-Tapia 2013, Sampaio-Barros 2006, El-Maghraoui 2011, Heslinga 2014, Forsblad-d’Elia 2013 ). The prevalence of IBD in AS ranges from 5-10% (El Maghraoui 2011). Less common extra articular manifestations include aortitis, pulmonary fibrosis, emphysema, conduction defects, ischemic heart disease and amyloidosis (Stolwijk 2014, Levy 2014, Brambila-Tapia 2013, Sampaio-Barros 2006, El-Maghraoui 2011, Heslinga 2014, Forsblad-d’Elia 2013, Huang 2013).

Diagnosis of AS

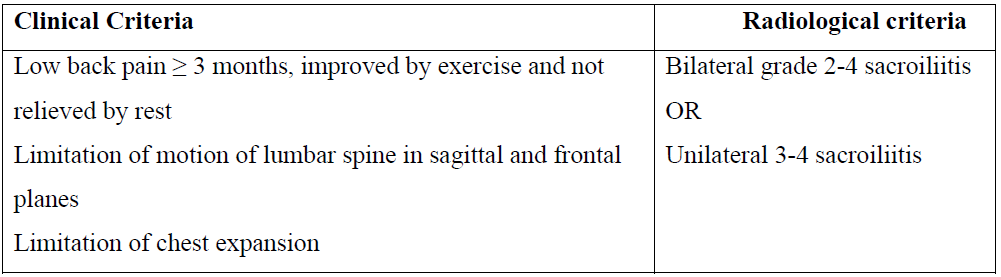

The diagnosis of AS is established when the patient has a combination of relevant symptoms, physical signs, and imaging findings. The most widely used and accepted diagnostic algorithm is the modified New York criteria (van der Linden 1984). Details are presented inTable 1.

Table 1: Modified New York criteria for AS

Disease course and monitoring of disease activity of AS

The natural course of AS is variable (Brophy 2002). Most patients have continuous disease activity with frequent clinical flares (Stone 2008,Kennedy 1993). Disease activity, functional status of the patient and structural damage are three important parameters that determine the long-term course of the disease. Hence various scoring systems have been developed to monitor the progression and also to study the response to therapeutic agents (Calin 1999, Spoorenberg 2004, Zochling 2011). BAS-G is a measure of the effect of AS on general well being (Jones 1996). Clinical disease and inflammatory activity are measured by scores such as Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) (Zochling 2011, Zochling 2008). BASDAI is calculated based on information regarding five symptom domains (Zochling 2011,Zochling 2008). The symptoms analyzed are pain with swelling in joints, fatigue, spinal pain, severity and duration of morning stiffness and discomfort with peripheral entheses. The scores ranged from 0-10.The physical function of patients is monitored by Dougados Functional Index (DFI), Health Assessment Questionnaire for Spondyloarthropathies (HAQ-S) and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) (Stone 2008, Zochling 2011). Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Mobility Index (BASMI) is an index used to reflect spinal mobility (Zochling 2011). Radiological severity of AS are measured by the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score (mSASSS) and BASRI (Wanders 2004, Mackay 2000). mSASSS is a cumulative score obtained by quantifying the changes at the anterior corners of the lumbar and cervical spine vertebrae (Wanders 2004).

Each corner is scored from 0 to 3 and the total scores range from 0 to 72 (Table 2). In addition,serum inflammatory markers such as ESR and CRP are used to monitor disease activity of AS.

Table 2: mSASSS scoring system

Management of AS

Treatment of AS involves multiple modalities. Physiotherapy and pharmacological measures are the mainstays. Pharmacological treatment is initiated by prescribing nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs have been shown to reduce pain and decrease inflammation in AS (Boulos 2005 and Poddubnyy 2012). NSAIDs may also be able to delay radiographic progression of the spine but this needs to be proven in future (Haroon 2012, Poddubnyy 2012 and Kroon 2012). Not all patients achieve complete disease remission with NSAIDs. Other medical agents used in the management of AS include corticosteroids, sulfasalazine and TNF-α inhibitors (TNFi) (Baraliakos 2012, Braun 2003, van der Horst- Bruinsma 2002, Braun 2011). Currently, TNFi are the mainstay of treatment for patients who do not achieve clinical remission with NSAIDs. Further, with the advent of the role of TNFi, the use of corticosteroids and DMARDs in patients with AS has become less common (Chen 2013,Spies 2009). A recent Cochrane review concluded that no strong evidence existed to support the role of methotrexate in the management of AS (Chen 2013).

Clinical features of AS