CBCT Advantages and Limitations

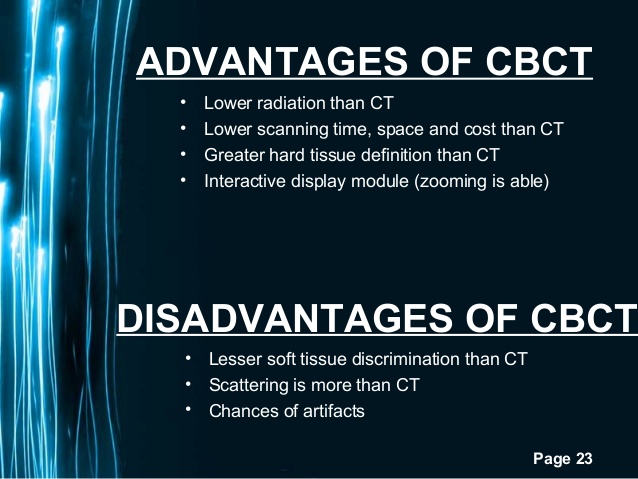

As discussed in previous sections, CBCT has been demonstrated to be an advantageous tool in dentistry, and more so in endodontics. This technology has been shown over time to be far superior to periapical conventional radiography. From detecting and measuring anatomical structures, pathologic findings to treatment planning, CBCT scans have many implications and uses. It helps show canal morphologies, accurate periapical status, pathologies of non-odontogenic origin, internal and external resorption, status of placed implants, and allows for measurement of anatomical distances when preparing for periapical surgeries. CBCT scans have low levels of radiation, comparable to periapical radiographs. Radiation doses for a CBCT scan can be as low as 7.3 microSeverts when compared to 6.3 microSeverts from a panoramic x-ray. CBCT at such a low dose help detect apical periodontitis allowing for better surgical anatomical assessment, trauma evaluation, canal anatomy, and root fracture identification. Under these considerations, it would be useful to take a preoperative CBCT scan prior to endodontic treatment or surgery. This helps to determine the location of different anatomical structures such as the inferior alveolar nerve, and also discern tooth and canal morphologies.

It would help detect accurately the presence or absence of apical findings, amount of bone loss and bony defects, and in cases of trauma, assess the severity of damage caused to the surrounding structures and the presence of horizontal root fractures. As with any technology, besides having useful applications, there are also pitfalls and limitations. Understanding the limitations is important to adequately utilize it to make diagnoses and prevent mistakes in interpreting the scans. Such as the case of metallic posts, which as Costa et al describes in their study, CBCT has good accuracy in detecting root fractures without metallic posts, but when they are present it significantly reduces the accuracy of detection. In this particular study, horizontal root fractures were found in 73% to 88% of the groups without metallic post present. With the posts, the accuracy was reduced to 55% to 70%. Highly radiopaque materials, gutta-percha, crowns containing metal, and amalgam restorations, will distort the CBCT scan causing reconstruction artifacts, scatter and beam hardening. Careful patient positioning and the optimum selection of scan parameters are the most important factors in avoiding image artifacts. Scatter and beam hardening distort the area affected by the presence of radiopaque materials, making it hard to diagnose properly, and misinterpretation of the scan. Clinicians evaluating the scans need to have the adequate knowledge and expertise to discern between beam hardening and artifacts, and true pathologic findings, such as root fractures. The simple fact that the scans need to be interpreted by clinicians of various levels of experience raises concerns.

Varying levels of experience and understanding shows that there will be variability when comparing interpretations between different examiners. This can be the case when evaluating follow up cases to determine success or failure, presence or absence of periapical radiolucencies, and root fractures. As early as 1972, Goldman et al showed that there was less than 50% agreement between 6 examiners evaluating success or failure and presence of apical periodontitis in conventional periapical radiographs. A later study corroborated these results, where there was substantial inter-observer and intra-observer disagreement existing in endodontic success and failure interpretation from periapical radiographs. For a much more complex technology such as CBCT, high levels of disagreements between observers is expected unless proper training and calibrations of each examiner is achieved. Otherwise, clinical interpretation research will be rendered invaluable due to the large discrepancies in interpretations. Huumonen and Ørstavik showed that the presence of a lesion is not always evident in its real extent and spatial relationships to important anatomic landmarks in periapical radiographs, making it important to eliminate such discrepancies even at a simple diagnostic level. In 2008, Estrela et al proposed a new CBCT based periapical index, which was reported to be more accurate than periapical radiographs in detecting apical periodontitis. This proposed index could standardize the diagnosis in order to increase accuracy. This CBCT periapical index (CBCT-PAI) would assist in calibrating multiple examiners when evaluating scans. It is a simple scale with scores ranging from 0 to 5.

The scoring is broken down as follows: a score of 0 indicates intact periapical structures, a score of 1 has a periapical finding with a diameter between 0.5 and 1 mm, a score of 2 has a periapical finding with a diameter between 1 and 2 mm, a score of 3 has a periapical finding with a diameter between 2 and 4 mm, a score of 4 has a periapical finding with a diameter between 4 and 8 mm, and a score of 5 has a periapical finding with a diameter greater than 8 mm. There are additional possible scores for the presence of expansion of the cortical bone (E) and for the presence of destruction of the cortical bone (D). When Esposito et al put the index to the test in 2011, three independent observers recorded the same measurements of the lesion for each plane examined (coronal, sagittal and axial). They attribute this result to the use of the standardized method for the 3D exploration of the lesions. They claimed that CBCT examination seems to be more reliable than conventional radiographs and that followup examinations can become more reliable using a standardized method like the CBCT-PAI is used to assess the lesions.

CBCT Advantages and Limitations