Automatic Identication of Redirects for Compromised Websites

Although there are certainly other ways to be hacked, one of the most obvious and easy to recognize as an observer is when a page is made to redirect to a page on another domain. Leontiadis et al. studied these search-redirection attacks within the search results of illegal pharmaceuticals. In the realm of luxury goods, this is when a website redirects to a counterfeit store. Obviously the real Coach webpage does not need to set random blog posts to redirect to it. When analyzing redirects, the easiest to detect are those redirecting due to an HTTP status code in the 300 to 399 range. When a requested webpage has a status code in this range it will reply with the code as well as the URL its content has supposedly been moved to. When the browser encounters this it will immediately try the new location without prompting the user or alerting them that anything is wrong. Redirecting with HTTP statuses is helpful for webmasters legitimately moving pages, but it’s also useful for maliciously driving traffic to external sites. Detecting these redirects can sometimes be as simple as requesting the header of a website.

Unfortunately webpages also redirect in other manners which don’t trigger until the page has already (at least partially) loaded in a browser. For example, one can be redirected via the HTML meta tag, or by a JavaScript call setting the \window.location” variable. Although one can parse HTML easily for a meta tag, sometimes offending JavaScript code is either obfuscated, packed, or buried deep within referenced scripts to the point of being very difficult (and time intensive on a large scale) to detect.

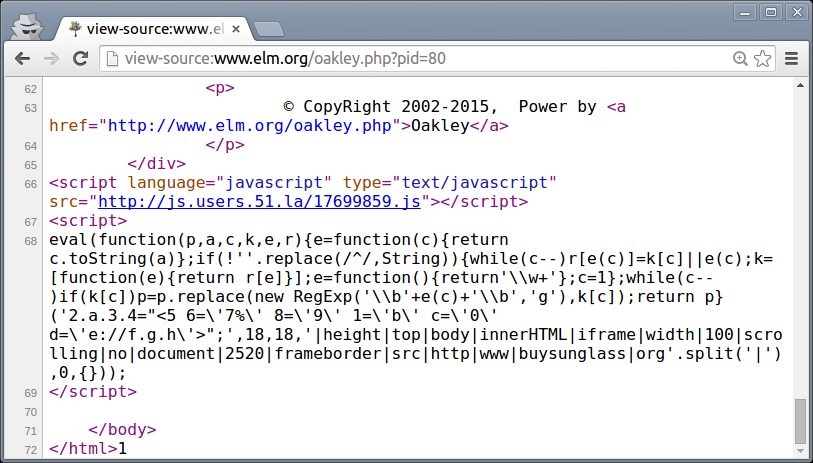

Figure 1: Example of packed JavaScript code which inserts an IFrame

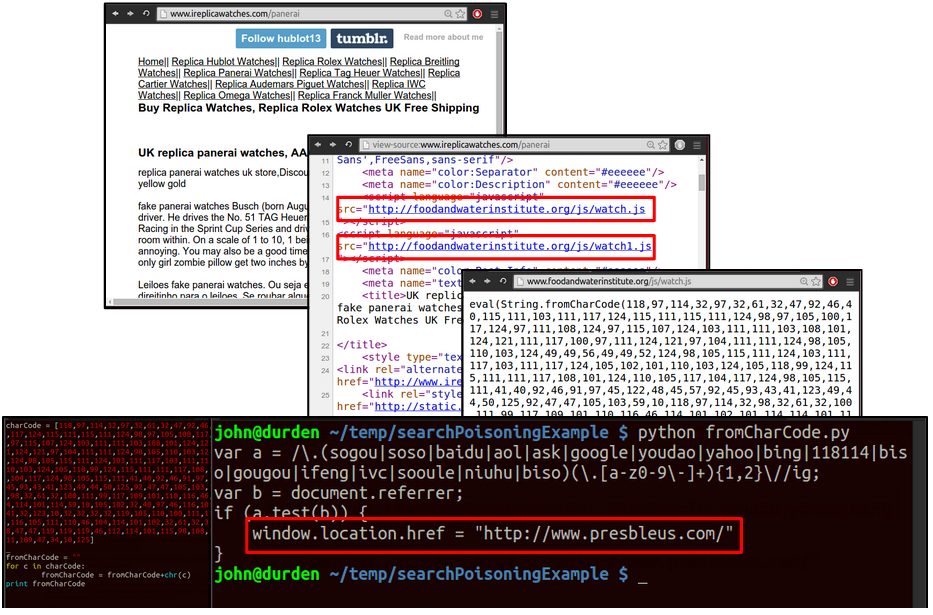

One way in which code can be obfuscated by hackers is the use of a code packer, as shown in Figure 1. Packers are an out-of-the-box solution for compressing code, which for hackers serve the purpose of obscuring the purpose of their code. Figure 2

re ects another way in which malicious JavaScript can be hidden. In this method, the characters of the offending code are stored as integers, only cast back to characters

Figure.2: Example of obfuscated JavaScript code which redirects visitors coming from a search engine.

when the page loads the script. Adding another layer of complication, sometimes a for loop is used to manipulate the arrays of integers in some fashion (for example multiplying every number by 5 before casting it back to a character). In doing this, hackers make the malicious code impossible to read by humans and make automatic detection difficult.

The most straightforward way to collect these non-HTTP redirects is to witness them occurring by allowing a page to naturally load and execute its scripts. Selenium is used once more to drive a Firefox browser in order to observe this redirecting behavior, Capturing the redirects encountered was performed with a custom Firefox plugin which listens for the tab’s \ready” event, recording the URLs seen. Figure 3 contains the relevant code. The \ready” event is red when a tab’s DOM1 is ready, at which point the tab’s URL attribute should contain the correct data

Figure 3: URLs seen by the tab are recorded to keep track of redirects

The list of URLs is communicated to a Python script via TCP, emptying after successfully being sent. Chains are considered/parsed after all URLs for a day have been visited to see whether URLs of outside domains were seen. Another consideration in encountering these redirects is that many will only trigger if the user is coming from a recognized search engine (see Figure 4 as well as Figure 2). This is a clever tactic, as anyone going straight to the URL (such as the owner of the webpage) won’t see anything out of the ordinary, while anyone who found it through Google is taken to a completely different website. This can make cleaning up hacked pages a bit more complicated, which can result in bad pages surviving longer.

To ensure these redirects were triggered, the Selenium browser also made use of another custom plugin which alters the header of all requests made so that the \referer” eld of all requests is set to https://www.google.com/.

(a) A JavaScript le is referenced before the opening HTML tag, suggesting the line

was injected.

(b) The referenced script checks whether the user arrived by search engine and

redirects them to a counterfeit store if so. Otherwise the visitor may be a bot, so

an iframe of the intended ending page is injected, something which a bot would be

much less likely to notice.

Figure 4: Example of JavaScript redirection seen in the wild.