Viral hepatitis B (HBV) is a silent public health problem. Globally, over two billion are infected with HBV, 360 million chronic carriers with an estimated 800,000 annual death by liver cancer/cirrhosis. 78% of liver cancer and 57% of cirrhosis is attributable to HBV. Prevalence rates of HBV vary from five to twenty percent in the developing world. Perinatal transmission

accounts approximately 15% of HBV-related deaths even in low endemic areas.India has intermediate endemicity with 2 to 8% prevalence, pooling 40-50 million chronic HBV carriers.

Lack of universal healthcare coverage makes long term treatment inaccessible and unaffordable in India and is a significant burden on patients. The Uniject or multi dose vial (with or without Vaccine Vial Monitor), monovalent or combined HepB vaccine for infants is universally available, cheap, and highly effective. It is considered as the first anticancer vaccine. It also prevents Hepatitis D Virus infection.

Several national and international guidelines recommend early immunization of Hepatitis B,starting at birth dose. In United States, The HepB vaccine birth dose is administered to infants during the birth hospitalization if mother is negative for Hepatitis B. [5] Infants of HBsAg positive mothers should receive hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) shortly after birth and should be immunized with monovalent HepB vaccine, preferably within 12 hours of birth. An infant bom to a mother with unknown HBsAg status should receive the first dose of monovalent HepB vaccine immediately after birth. Immunization Handbook for Medical Officers 2008 released by Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India recommends birth dose as early

as possible within 24 hrs irrespective Hepatitis B status of mothers, to prevent perinatal transmission.

Hepatitis B in pregnant women

How to raise HepB birth dose is a global challenge. WHO document – “Practices to improve coverage of the hepatitis B birth dose vaccine” narrates detailed measures. Realizing the public health importance and to overcome the lapses, the World hepatitis day was launched on 28th July since 2010. On WHO recommendations, HepB vaccine for infants was introduced nationwide in 183 countries and a birth dose for HepB vaccine was introduced in 93 countries by the end of 2013. The global coverage of HepB birth dose vaccine was estimated at 38%, ranging from 11% in African region to 79% in the Western Pacific by 2013. It was 30% and 33% in 2012 and 2013 respectively in India.

The primary outcome in this study demonstrated an overall HepB Birth Dose coverage (56.1%) in the Dakshina Karnataka and neighbouring districts from April 2013 to March 2014. In the study cohort, 30.57% and 11.7% of newborns permanently missed the opportunity for HepB birth dose in the four planning unit area and the Medical College respectively. Another 7.22% and 35.3% received birth dose after 48hrs but before discharge in the planning units and Medical College respectively. In this study, it is observed that some pioneer institutions are administering zero OPV but not HepB birth dose vaccine and BCG. However, high female literacy, small family norm, more women empowerment etc has minimized gender disparity in our study area supporting Millennium Development Goal 2000 goals/strategies (Table 4).

One third o f the infants acquire HBV parentally from carrier mother, remaining two thirds from horizontal transmission via service providers/visitors and or medical errors. Vaccination reduces the rate of chronic infection from 8-15% to less than 1% and can potentially avert 4.8million HBV related deaths over a 10 year period. Given that adequate vaccination of infants, starting with birth dose followed by timely 2 to 3 regular doses can even eliminate HBV. [14] Denying or delaying newborn vaccines means disregarding NIS.

It was observed that physicians practicing in government sectors were more likely to administer Hepatitis B Birth Dose within 24 hours of birth than those in private sectors. However, the finding of our study showed that there was no significant difference between practice setting when it comes to BCG and zero dose OPV. It was noted that many private institutions administer HepB Birth Dose twice a week for ‘administrative ease’. This has likely contributed for non-adherence of recommendation. Additionally, “Mercurial myth” still exists strongly even among the learned.

Decision to delay the birth dose and subsequent doses of HepB vaccine widens population immunity gap and predisposes infants who potentially have been infected with HBV to chronicity and its the complications in their productive age group. Delay in implementation will make this queue longer day by day. Also, accelerated immigration of

Indians across globe significantly contributes to global health burden. Most children who die within the first month of life have serious conditions that are recognized at birth or shortly afterwards who are less likely to receive a birth dose of HBV

vaccine” making it a public health emergency. Responding to the Global concern of raising HepB birth dose vaccine, intervention (as already described) was launched in Rural Medical College raised the coverage from 19% in April to 100% in July 2014 and sustained. It has become the part of newborn care protocol like cord care,

eye care, Vitamin K administration, early breast feeding etc. Coverage of zero OPV and

BCG also rose from 94% in April to 100% in July 2014. There is huge opportunity to raise

Hepatitis B birth dose coverage in a revolutionary mode through simple do-able measures,

making it integral part of the newborn care protocol. Private sectors merits

multidimensional and systemic advocacy.

WHO, NIS and IAP recommend birth dose as early as possible within 24 hours. Health Management Information System (HMIS) of Government of India qualifies birth dose within 48 hours as timely vaccination. Further, manufacturers of vaccines also recommend HepB to be administered ‘before discharge’ has created ambiguity among service providers. Some service providers in Govt set up, adhering strictly to the NIS, did not provide Hepatitis B birth dose vaccination beyond 24 hours of birth despite suffering unavoidable delays. On the other hand, Pvt sector was not so religious, often administered after 48 hours or just before discharge, affecting the efficiency of prevention. There is a need to standardize newborn vaccination protocol to be displayed for uniform practice universally and avoid confusions.

During the study, we additionally noted that 20% (301) infants bom in Pvt facilities made excursions to nearby Govt facility for newborn vaccination. This puts the newborns at risk for hypothermia and infections (risk is not quantified in this study as it is beyond the scope). This is not in compliance with the newborn vaccination protocol which recommends vaccination during the observation period in the labour room or newborn comer before shifting to the postnatal ward.

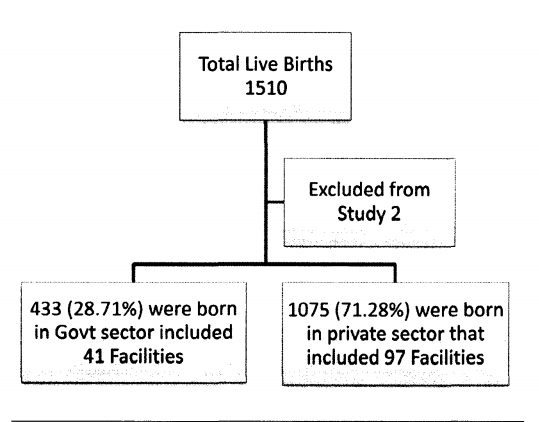

Strengths of the study include the sample population of Hepatitis B birth dose in varying community and academic practices, in total representing 97 Private hospitals and 41 government hospitals which is representative of the practice at Dakshina Kannada, Kodagu and Udupi district. Inclusion of only institutional deliveries and very high rate of institutional deliveries increasing the reliability o f the data. Also, extended immunogram increased the accuracy o f data. This study is not without limitations. We did not consider socio-economic status and affordability of population which might have contributed in

decision making of Hepatitis B birth dose.

In summary, we concluded that in the given population, the Hepatitis B birth dose coverage was inadequate, more so in the Pvt. sector. Efforts to adhere to standardized Hepatitis B birth dose protocols may relieve the coming generations of Hepatitis B burden. Additionally, conducting studies or surveys to assess the knowledge, attitude and practice of HepB Birth Dose vaccination among service providers can be an eye opener to explore factors contributing to inadequate coverage.

Demography o f the study population