Introduction

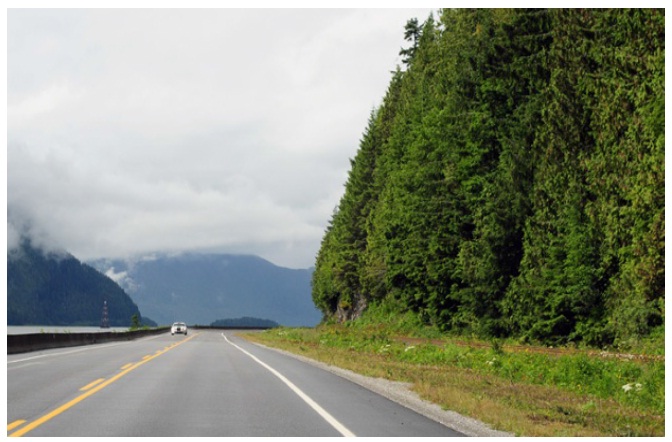

Aboriginal populations typically constitute one of the most vulnerable groups, both globally and in Canada, as they often live in remote, isolated, and highly impoverished communities. Because of these conditions, “their exposure to risk factors is often much greater than non-Aboriginal populations. Hence, their risk of exploitation is much higher. There are numerous cases domestically and globally that could be used to highlight the violence perpetrated against Indigenous populations. One example is “The Highway of Tears”, a stretch of highway between Prince George and Prince Rupert in British Columbia, Canada that between 1969 and 2011 involved a series of unsolved disappearances and murders of women, mainly of Aboriginal status.4 Another example is the trafficking of Aboriginal women from Thunder Bay, Ontario to Duluth Port, Minnesota via US ships.5 Despite the prevalence of these crimes, it seems as though little is being done in the way of recourse for these women. Of late there has been increasing awareness of the sexual violence against, and trafficking of, Aboriginal women. Historically speaking, Canada has an abhorrent record regarding its treatment of Aboriginal populations that unfortunately continues today. The lack of regard towards Aboriginal populations helps foster the very conditions (such as poverty, substance abuse, and systemic racism) that give rise to youth and adults vulnerable to human trafficking and sexual violence. Victor Malarek, a Canadian investigative journalist and author, notes that, “where vulnerable youth and adults need money or goods in exchange to survive, they will be regarded, treated, traded and used as common commodities.

Figure 1. Highway 16, also known as the “Highway of Tears”, due to the many Aboriginal women who have gone missing along this road. Photograph: Lyndsie Bourgon, “As murders and disappearances mount, Canadian women ask: Am I Next?

Analytical Approach

I employ a critical global studies perspective that enables me to explore a local issue and map it to wider global processes and interactions. As articulated by Mark Juergensmeyer, this approach promotes a transnational understanding of events, ideas and trends, emphasizing that what appears local can actually be indicative of wider global processes. For instance, though my discussions on human trafficking, sexual violence and colonialism are focused on the national scale, they are but a microcosm of larger, international problems that stretch well beyond the confines of one particular nation state’s boundaries, government, or cultural customs. For instance, an example outside of Canada is the colonization of Australia and resulting “Stolen Generation”, where thousands of Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their homes, never to return. Many of the same problems that Canadian Aborigines face plague Australian Indigenes, as well as Indigenous groups in the United States, New Zealand, and elsewhere. Understanding the factors that contribute to the marginalization of specific communities (i.e. Aborigines) will aid in understanding why they are targeted and where change needs to be made. Thus by examining a local issue in such depth, I am able to draw parallels between, and explore the implications for, the local, regional, national, international, and wider global contexts.

Conquest: Sexual Violence and American Indian Genocide

Smith applies the intersectionality paradigm to her work, as evidenced by her opening statement that, “women of colour live in the dangerous intersections of gender and race. Intersectionality is the study of intersections between various systems of domination, oppression, and discrimination. Rather than studying these systems of oppression separately, inter sectionality explores how they mutually construct and reinforce each other. These interlocking systems of oppression create a matrix of domination, reflecting the organization of different social classifications and how they are supported by political, economic, and ideological conditions. Race, gender, and class are the ones most commonly referred to but systems of oppression can also include age, sexual orientation, religion, and ethnicity. While the theory was originally developed to examine systems of oppression faced by African American women, it no doubt affects other groups essentially any category of human labeled ‘other’.